“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it, he who doesn’t, pays it.” Albert Einstein.

What does it mean and why should I care?

Often termed a financial ‘miracle’ by financial professionals and economists; put simply compounding return is the ability to earn a return from your original investment as well as a return on all returns and interest received since the original investment – the gain on the gain. This compounds year on year leading to exponential growth on the original investment.

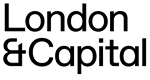

Taking an investment of £1,000 receiving 10% guaranteed every year for the next 30 years. In each year, the return is £100 on the original investment. However, by reinvesting the £100 each year the return gradually gets higher and higher than £100 even though no new funds have been added to the investment other than the initial £1,000.

Source: London & Capital (Example for illustration only)

If the annual return was not reinvested, meaning no compounding return effect takes place, the ending market value after 30 years is £4,000.

By reinvesting the return and taking advantage of compounding returns the ending market value after 30 years is £17,449.40.

Compounding returns is an extremely powerful tool which can be employed when managing portfolios for long term investors to generate wealth. It is one of the key aspects of our investment management approach at London & Capital and we actively look for ways to enhance and build upon its features when making investment decisions.

Maximising the compounding effect in long term portfolios.

A ‘miracle’? Maybe. But financial markets do not always go up, returns are not guaranteed, and the ride to get there is certainly not linear. Two ways you can erode the benefits of compounding returns include:

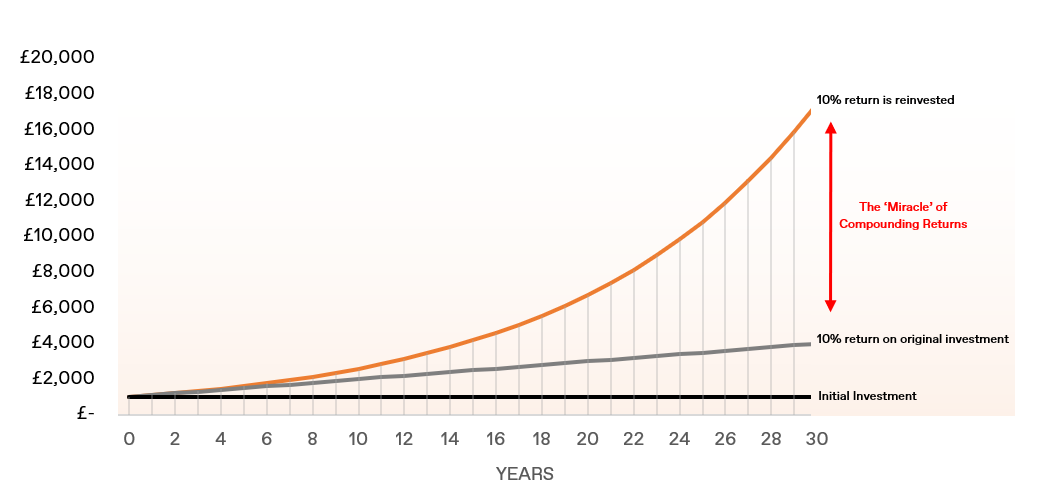

Dispersion of returns

When returns are unevenly distributed the compound return is negatively impacted. Even if there are multiple years with very high returns, a stable return provides the highest compound return in the portfolio.

Source: London & Capital (Example for illustration only)

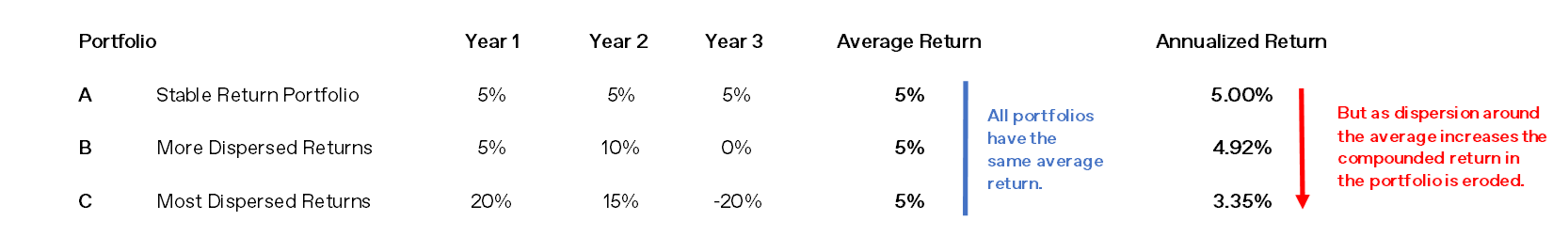

Negative returns

When a portfolio experiences negative returns, the required return in subsequent years is increased to maintain a target annualized return. Larger negative returns equate to significantly more pressure on the portfolio to perform in the recovery to meet the target annualized return. In the below example, the three portfolios target a 4% annualized return.

Source: London & Capital (Example for illustration only)

So how does one maximise the compounding effect?

The answer is obvious really, buy investments only when financial markets are going up and liquidate just before they are going to crash, right? Thank you magic genie, and for my other two wishes can I please have a luxury holiday in the Maldives and a private jet? Timing the market perfectly comes down to nothing more than luck and we prefer not to gamble on such uncontrollable endeavours.

We believe that the compounding effect of returns can be maximised by creating portfolios that naturally perform more defensively in times of market distress (less negative) and behave less volatile (less dispersion) at all times. This is achieved by identifying and investing in companies that exhibit key characteristics such as clear recurring revenue streams, a leader in their industry, low levels of debt, high customer retention and many more. By participating less in market contractions and volatility, the portfolios have to do less work to get back to the level they were before the market contraction and the compound return is less negatively impacted.